Frantz Fanon

Documents

Links

Keywords

Share

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Grove, 2002.

Publisher’s Presentation

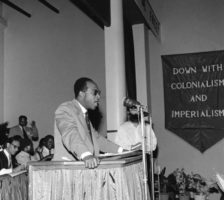

“A distinguished psychiatrist from Martinique who took part in the Algerian Nationalist Movement, Frantz Fanon was one of the most important theorists of revolutionary struggle, colonialism, and racial difference in history. Fanon’s masterwork is a classic alongside Edward Said’s Orientalism or The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and it is now available in a new translation that updates its language for a new generation of readers.

The Wretched of the Earth is a brilliant analysis of the psychology of the colonized and their path to liberation. Bearing singular insight into the rage and frustration of colonized peoples, and the role of violence in effecting historical change, the book incisively attacks the twin perils of post-independence colonial politics: the disenfranchisement of the masses by the elites on the one hand, and intertribal and interfaith animosities on the other. Fanon’s analysis, a veritable handbook of social reorganization for leaders of emerging nations, has been reflected all too clearly in the corruption and violence that has plagued present-day Africa.

The Wretched of the Earth has had a major impact on civil rights, anti-colonialism, and black consciousness movements around the world.”

Homage to Frantz Fanon

By Aimé Césaire

Frantz Fanon is dead. We expected this for many months, but against all reason, we were hopeful. We knew him as such a determined person, capable of miracles, and as such a crucial figure on the horizon of men. We must accept the facts: Frantz Fanon is dead at age 37. A short life, but extraordinary. Brief, but bright, illuminating one of the most atrocious tragedies of the 20th century and detailing in an exemplary manner the human condition, the condition of modern man. If the word “commitment” has a meaning, then it is embodied in the person of Frantz Fanon. He was called “an advocate of violence, a terrorist.” And it’s true Fanon appointed himself the theoretician of violence, the sole weapon of the colonized against the barbarism of colonialism.

However odd it seems, his violence was non-violent; the violence of justice, of pureness, uncompromising. His revolt was ethical, his approach one of generosity. He did not simply join a cause. He gave himself to it. Wholly. Without reserve. Without measure. With unqualified passion.

A doctor, he knew human suffering. As a psychiatrist, he observed the impact on the human mind of traumatic events. Above all, as a “colonial” man he felt and understood what it was to be born and live in a colonial situation; he studied this situation scientifically, aided by introspection as much as observation.

His revolt was in this context. As a doctor in Algeria, he witnessed the unfolding of colonial atrocities, and this was what gave birth to rebellion. It wasn’t enough for him to argue in defense of the Algerian people. He united himself with the oppressed, humiliated, tortured and beaten down Algerian. He became Algerian. Lived, fought and died Algerian. A theoretician of violence, doubtless, and yet more so of action. Because he had an aversion to mere talk. Because he had an aversion to compromise. Because he had an aversion to cowardice. No one was more respectful of ideas, more responsible to his own ideals, more exacting of life he imagined as a practical ideal.

It is thus that he became a combatant, and a writer, one of the most brilliant of his generation.

On colonialism, the human consequences of colonization and racism, the key text to read is Black Skin, White Masks. On decolonization, again by Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth.

Fanon died and one reflects on his life; his epic side as well as his tragic side. The epic side is that Fanon lived to the very end his destiny of a champion of liberty, mastering to the heights his sense of identity with humanity and that he died a fighter for Internationalism.

At the actual moment when he himself was entering the “great darkness,” at the brink of which he was reeling, he understands: “Come Comrades, it is better to change our thinking. To shake off and leave behind the great darkness into which we have plunged… It is necessary to invent, to discover … for Europe, for ourselves, and for mankind, … to develop a new way of thinking, to try to bring forth a new humankind.

I don’t know of anything more moving or greater than this lesson of life coming from a deathbed.

Présence Africaine, no. 40 (1962); translated by Connie Rosemont