How to Contribute to Iberian Connections

Iberian Connections is sponsored by The Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies, and the Department of Spanish and Portuguese.

Students and participants in this seminar will write frequently. They will also read and review each other frequently. Reading and writing, all of us will abide by two main principles: peer review, and generous thinking. Peer review means that our mission is to work within a community of scholars led by a sense of equity —hence, we are peers, there is no hierarchy among us when we are working together. Generous thinking —the subject of a recent book by Kathleen Fitzpatrick— means that instead of reading each other with a blind critical eye to “tear apart” mercilessly, we need to engage with each other’s writings with the ability to think with each other, contributing to the improvement of the work we do individually [1].

After careful peer review, some of these writings will be posted and credited to the author on the relevant section of Iberian Connections. Those who publish their work on Iberian Connections need to know that the ideas contained in their online publication are their sole property, and that they can re-use them and publish them in their own research papers, articles, or dissertations. Likewise, if other students and researchers want to use the ideas and theses published online, they need to credit them by author, title, and all other relevant details of publication, like they would do with any other printed publication. Finally, all material published online is protected by attribution to their authors and timestamp —in other words, publishing online is a safe way to expose ideas and theses while sharing them with a community of scholars, not a way to give them away freely and unsafely.

Here is a list of kinds of writings participants can do for this seminar:

Article

Articles are paper-like monographs, with an extension of around 8,000 words, with footnotes and bibliography. Articles are directly related to the list of texts and subjects included in a particular session. For instance, if the seminar session includes readings from Christine de Pizan and Diego de Valera, and the main subject is peace, you can write an article on one (or several) of these three elements. But if you want to write a text on some other text by one of those authors, then it won’t have the category of article, it will fall in a different category (see Note) and will have a different extension.

Note

Notes are like articles, but they are only indirectly related to a specific session (for instance, they deal with one of the authors of the reading list, but the main subject or the main text of reference are not on the list), and will be shorter (around 3,000 words, with footnotes and bibliography).

Gloss

A gloss is a critical interpretation of a cultural, theoretical concept. Such concept is in itself a critical decision. If you want to identify a concept, you do not have to limit yourself to a specific list already sanctioned by the canon. You can identify other kind of concepts. For instance, you can identify concepts that seem marginal, tropes, metaphors, or fictions, casually used but that may direct to more complex cultural, political, legal issues; visual or musical concepts that point to cultural issues and problems; literary concepts that try to find their way into the cultural realm in order to submit it to criticism; etc.

This is a multilingual database. Please feel free to suggest glosses in different languages and from different periods, and, by all means, cross cultures, periods, and political and legal systems when you are writing your gloss if it is relevant for your gloss-writing. Do not be afraid to suggest the original concept in the original language and script –and provide your reader with a transliteration and a cogent translation.

How to prepare your gloss

- Title: Identify the concept you want to write about. Use the concept only as your title.

- Date or date range for the concept: identify the moment of creation, or the moment in which a certain word becomes a concept, etc.

- Location: it normally corresponds with the place of production of the primary source(s) you are using.

Content of the gloss:

- Identify the primary sources for your concept of choice

- Establish its genealogy or history

- Discuss its interpretations and more salient bibliography

- Create your interpretation by exploring the concept using critical and theoretical discourses. Ask yourself how this concept can be interpreted as a theoretical concept itself, and how can it be productive (if it can) for contemporary critical thought.

- Elaborate a bibliographical list with primary and secondary sources, using MLA models.

- Elaborate a list of related hyperlinks.

Review

Typical reviews engage with a critical reading of a book, an article, a small set of bibliographical items about one specific theme, or even other resources like video, video games, computer games, digital humanities projects, and other. Keep your work short and generously critical (remember the generous thinking part).

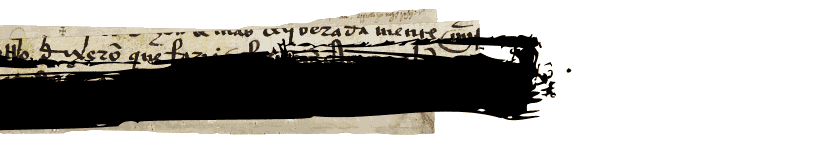

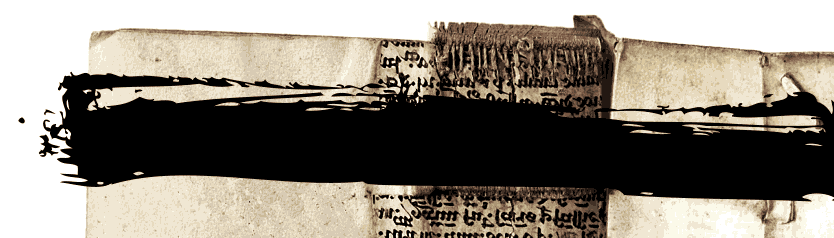

Library Item

A library item is a trace of your work with primary sources in the library. This will contribute to a larger database of primary materials. For your library item please register the following information:

- Title (of the work, if it has one; if not, the one you give it to it)

- Short description (a teaser of what the reader will find in your contribution)

- Detailed description (here you can be completely free in what you register, and please do not hesitate to present theses, ideas, and be creative)

- Location (the place where the work was produced, if known).

- Date (or range of dates of the item)

- Alternate title (if it has one; for instance, the Libro de Buen Amor is also known as Libro del Arcipreste)

- Author(s), translator(s), compiler(s), glossator(s)

- Patron

- Workshop (for instance, the workshop that worked for Alfonso X)

- Scribe identity

- Transcription (maybe it is not a complete one, but it transcribes fragments or excerpts that you judge important)

- Bibliography

- Citations (MLA citation of the item)

- If manuscript: paper? parchment? does it have glosses? does it have images?

- If printed copy: printing press and printer.

- Library, city where the library is, call number, link to catalog or links to other databases that register the item

- Link to digitized version

- Additional links or resources

In addition to this, there are other forms in which you may contribute to the seminar and Iberian Connections:

Interviews

Throughout the year we will have guests visiting our seminar and discussing their work with us. Please consider setting up an appointment with them for an interview on different subjects (research, academic life, administration, the humanities, etc.) You may record this interview in many ways, including audio and video. Please review carefully the relevant protocols governing interviews, and prepare your questions in advance [2]. You can consult the questions with your peers (us) and you can engage some of your peers for the interview (one can take pictures, or participate in the recording of the event, alternate asking questions, etc.)

Podcasts

If you want to prepare a podcast of any subject related to our seminar, do not hesitate to do it. For instance, a discussion about a particular subject that you prefer to record rather than write; a debate with a peer; an analysis of a musical item that obviously needs sound; etc. A short, around 3‑minute-long podcast can be very effective, and will help you engaging your audience about one particular subject, not unlike a “lightning-talk” or an “elevator pitch”.

Videocasts

Same as before, but with video.

Furthermore, there are other ways in which you can participate

Presentations

General presentations for the class (like, for instance, preparing an intervention for the class, with A/V, and then posting it online).

Galleries

You may want to gather a number of images and do an online exhibit with them.

Responses

Prepare a response for one of our seminar sessions, a peer, or one of our guests.

Virtual colloquia

If you want to collect several discussions about one particular subject and create a cluster of articles or notes about it.

If you have other ideas, do not even hesitate to present them. Also, you can combine several kinds in one (for instance, you can videocast a library item)

Notes

- Kathleen Fitzpatrick. Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach to Saving the University. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019.[↑]

- There are many ways to conduct interviews, as well as many different possible protocols. This link from Columbia University J‑School seems an interesting starting point, but you will find many other resources online. Do not hesitate to create your own and maybe share them with the other participants. Some central points, however, include the following (from the link I just recommended): “The rules that govern the reporter’s behavior in the interview can be detailed with some certainty. Reporters, too, conceal, mislead and, at times, lie. Few reporters justify these practices. Most agree the reporter should:

- Identify himself or herself at the outset of the interview.

- State the purpose of the interview.

- Make clear to those unaccustomed to being interviewed that the material will be used.

- Tell the source how much time the interview will take.

- Keep the interview as short as possible.

- Ask specific questions that the source is competent to answer.

- Give the source ample time to reply.

- Ask the source to clarify complex or vague answers.

- Read back answers if requested or when in doubt about the phrasing of crucial material.

- Insist on answers if the public has a right to know them.

- Avoid lecturing the source, arguing or debating.

- Abide by requests for nonattribution, background only or off‑the-record should the source make this a condition of the interview or of a statement.

Reporters who habitually violate these rules risk losing their sources. Few sources will talk to an incompetent or an exploitative reporter. When the source realizes that he or she is being used to enhance the reporter’s career or to further the reporter’s personal ideas or philosophy, the source will close up.”[↑]