Margo, ‑inis

By Jesús R. Velasco | Published on August 12, 2019

Links

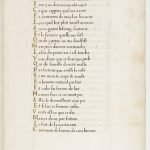

- Christine de Pizan, Livre de la Mutation de Fortune. Arsenal Library, Paris, ms 3172.

- Agamben, the contemporary

- Rony Klein, D’une redéfinition de la littérature mineure

- Deleuze & Guattari, Minor literature

- Murad Idris, War for Peace

Keywords

Share

Margins or marginal writing may have various meanings. The word “margin” derives from Latin margo, which refers to many sorts of edges and borders. In the first place, it probably meant to signify the land’s edges. For instance, the word referred to the sides of the riverbed (also ripae); in agriculture, the margo would refer to the part of the field that is not intended to be plowed up into furrows. The margines of the field need to be kept clean and without bad weeds that could damage the crops. As an uncultured, but cleaned space, it is in the transitional realm between natural, unmanaged ecosystem, and the artistic, agri-cultured space. Yet, those margins are highly technical, they constitute a cordon sanitaire that not only separate the weeds from the crops, but also allows the agricultor her or himself to cross through the fields, to put away the tools for later use, to rest, eat, drink, etc. The margin is not a clearing in the forest, but it is, indeed, a clearing separating the cultured fields from the rest of the land.

Writing as labor

The unknown monk, author of an indovinello or riddle found on a manuscript of Iberian origin in Verona, wrote this (making a rhyme mistake?):

Se pareba boves

alba pratalia araba

albo versorio teneba

negro semen seminaba

(Leading the oxen in from of him, he plowed white fields, holding a white plow, and sowing black seeds.)

Writing is a manual labor in which the empty fields of the page need to be plowed with the strange tool that sows the seed of thoughts —words, ideas, all of them in black ink. The text was found on a marginal place, a space of the book that was not supposed to be used for writing, the first blank page, or flyleaf (in Spanish página de respeto or página de cortesía). The monk has probably used it to check his tool, to see whether the quill or calamus, the stylus, or whatever other instrument he was using worked properly. This is called a probatio pennae or probatio calami.

Contemporary authors, including Jacques Derrida or Cornelia Vissman, have also used agricultural metaphors of plowing and sowing a field to speak about writing. For Vissman, the legal preamble is the furrow that establishes the limit of the city and civic life, as she explains in her Files [1]. Maybe because of this metaphor we live by (writing is laboring a uncultured land to yield some kind of production) [2] margins are the blank sides of the page, and marginal writing what runs across them in the form of textual (or other) interactions involving, also, several kind of contents and functions.

Metaphors do not stop at a first degree and they can pile up one upon the other, so margin and marginal writing also has social, political, and other meanings that we want, at least, to mention, so that we can set an order to our discourse: we want to know what are the things we refer to when we use a series of semantic fields. We, in fact, need to disentangle those metaphors, to see which ones are the ones that seem productive for our purpose, and which ones can also be put away at the margins of our work.

Peace

Why would the more or less abstract and amorphous theme of peace would help us at all achieving this mission of working out a theory of marginal writing and microliteratures? As Murad Idris has recently argued, there is a disjuncture within the very articulation of the concept of peace. While it purports always to be an eternal, universal, general concept, close readings of the theories of peace that vow for this universality show, rather, that the concept of peace holds a parasitic relationship with other ideas and political programs. In other words, rather than being universal and eternal, peace is provincial, it is a concept carefully crafted each time in specific conditions (political, legal, theological), in order to convey other political actions (for instance, war).

The concept of peace achieves this because it also configures each time its own semantic relations, that it insinuates, carries with it: friendship, companionship, common good, wellbeing, tranquility, orthodoxy, salvation, and many others, which are neither always the same nor can be always defined in the same way. On the contrary, they are multifaceted ideas that seem similar, but are extraordinarily different in the way they establish its network of political, legal, and theological actions.

Peace is at the center of political, legal, and theological discourse; it is even at the center of the discourse of war. And yet, it is entirely marginal, external, a furrow, if your wish, from which one could cultivate the land of politics in many different, contradictory, paradoxical ways. One could say, in this sense, that one characteristic of the concept of peace is its central marginality, or, maybe its marginal centrality. Those are some of the reasons why maybe the concept of peace can provide us a vantage point to look at microliteratures.

Two contemporaries

There is, however, a second possibility. Let’s take two more or less peripheral medieval authors who, in the midst of civil war, decide to create a discourse on peace. And yet, not on peace in a general way, but rather this peace, the peace of this moment in particular. They are not only political writers, they are contemporaries, insofar as they decide they can intervene, somehow, in a pressing present, constituting a profound dissonance [3].

One of those authors is a woman, Christine de Pizan. As you can see in the image of the manuscript, sees herself in the middle of a transformation: she is the one who speaks, she says, the one who from woman, was turned into a man, both in body (corps) and in face (voult):

Homme suis ie ne ment pas

Asses le demonstrent mes pas

Et si fus ie femme iadis

Verite est ce que ie dis

Mais ie diray par fiction

Le fait de la mutation

Comment de femme devins homme.

(I am a man, I do not lie, / and I used to be a woman. / It is true what I say, / but I will explain through fiction / how I became a man, being a woman.) [4]

She had to become a man to earn her life as a political writer for queens, kings, princes and princesses. But she always kept a certain marginal position, and was heavily criticized mainly for being a woman and yet doing what she did. She was always concerned about the creation of her texts and the creation of the manuscripts that would hold them, designing the layout, the material characteristics, and the images that, in some cases, would need to accompany both her central text and her own marginal writings (in form of glosses or allegories, for instance). Some of her political, textual interventions indicate her interest in peacemaking, and her Livre de paix, or Book of peace, the one we are reading for this seminar session, is fully devoted to the question of peace in the midst of a civil war.

In similar circumstances writes another partially peripheral author, Diego de Valera, a plebeian of converso origin (his father, the medical doctor Alonso de Chirino, had converted from judaism to christianity). Diego also writes frequently in text and glosses, using all the available spaces on the surface of the page, and his Exhortation to peace is not an exception. Likewise, his interest is to create a marginal set of references that would allow the reader to find the theme of peace in his library, among the books he already owns —and has most probably not read.

Littérature mineure

Those are the conditions in which we intend to explore the theory of marginal writing, microliterary attitudes and microliterary, contemporary dissonances. To do that we will find some theoretical support reading a small part from Deleuze & Guattari’s short book on Kafka: pour une littérature mineure, and we will see whether the idea of minor literature is productive here to help us in this project.

But more importantly, we will begin here a theoretical investigation that will accompany for the duration of this seminar, all semester long: we will be like poachers who are on the look out for concepts, expressions, sometimes casual considerations from our primary sources, sometimes verbal ones, sometimes material or imaginary ones. We will underscore them and work with them, to see whether we can build a theoretical vocabulary (a glossary, if you wish) with their own production —rather than applying well-known and used concepts from our canon of theorists.

Notes

- Cornelia Vissman. Files. Law and Media Technology. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2000.[↑]

- See George Lakoff and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.[↑]

- Giorgio Agamben. “What is the Contemporary?” In Giorgio Agamben, What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2009: 39–54[↑]

- Christine de Pizan, Livre de la mutation de fortune, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Paris, ms. 3172, fol. 4r.[↑]