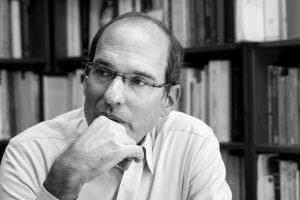

David Nirenberg

The interview with David Nirenberg took place on December 12th, 2017, in his professorial office at The University of Chicago. In addition to being Deborah R. and Edgar D. Jannotta Distinguished Service Professor of Medieval History and Committee on Social Thought, David is also the Executive Vice-Provost of the university. He served as Dean of the Social Sciences for a number of years.

I have had the chance to have many conversations with David for years, but this is the first time that there are recording devices between us —a voice recorder, two digital cameras, and a film camera. There is also artificial light that adds to the Winter pale light entering through the window. There is, of course, the irrepetible moment, after a long administrative meeting, part of his everyday daily job. I know that to gather the necessary intellectual energy to face this daily administrative job, David wakes up very early to work for a few hours in one of his current projects, which in this moment is a book he is coauthoring with his father, the Mathematician Ricardo Nirenberg, of Albany, on sameness and difference.

Maybe his first experience in academic freedom happens during those wee hours of the morning, when he fills up the matera and starts sipping the yerba mate, refilling it with water at the repetitive and different rhythm of the readings and the production of writing. He is surrounded by a city of books in a host of languages. At the beginning of one of his last publications, his book Anti-Judaism, he explains that his relation to languages: he will use many of them, including Greek, Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, German, Spanish, and other modern and ancient languages, only insofar as he is able to work with them firsthand, with no need of translation. Maybe this is the second fundamental experience of academic and intellectual freedom for David: being able to get fully immersed in a sea of languages, to dialogue with large, old and new traditions to which he want to ask very difficult and meaningful questions.

Universities privilege oftentimes incremental knowledge, rather than revolutionary findings, David says. Inherited fields of study are soft but pervasive forms of oppression weighting heavily on the minds of researchers. This oppression is perhaps the first barrier to academic freedom. But this oppression is only partially institutional. David considers that, within the institution, what is most difficult to achieve is the necessary solitude we need to think. If there is something I want to gather from this interview is his focus on that particular need of solitude and time, the need, therefore, to be able to be the master of one’s own rhythm.