peninsula

¶ What does it mean for a culture to be peninsular? This is not, or not just, a disciplinary question for Peninsularists with a capital P, for those who toil in lands known, more or less synonymously, as “Iberia.” No, the question is about peninsulas—in minuscule, and therefore bigger—and the implications of the geographical formation itself. To answer this and the following questions means navigating a perilous strait, with the subsequent risk of hitting a dead end.

- Land’s end.

¶ What lessons does a peninsula hold? Lessons that lurk, peninsula-like, at the end but also the beginning. Lessons that are appended to other lessons, suspended by other questions. Lessons that have become lodged in an outgrowth, an offshoot, of a larger mass. Lessons that are stuck at the bottom, that the heart strains to pump back up and out of a torpid, numb, or swollen limb. Lessons whose incorporation into the rest of the body risks poisoning, contamination, and contagion,

- but also renewal.

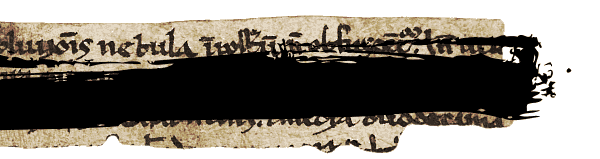

¶ What makes a peninsula, a peninsula? Its shape: it’s a body of land surrounded on three sides by water and connected to a larger landmass. A projection, protrusion, or protuberance. It is the stem hanging from the typographical bowl in the letter “P” itself. But it is not totally clear what distinguishes a peninsula from other land masses of varying sizes that share this definition—a cape, a bill, a spit, a point, a promontory, a headland, a subcontinent. Peninsulas are ambiguous, amorphous, and subjective. They are constituted inevitably by their relationship to adjacent lands and seas, defined less by their morphology than by their dependency. They exist asymmetrically, always relative to something larger, thus summoning relationships at once historical, political, symbolic (symbiotic, parasitic, exploitative). Peninsulas are tangential to the mainland.

- They are a corollary, a dangling signifier.

¶ Why is Iberia the Peninsula? Look up “peninsula” in the dictionary, and you’ll find yourself tossed back to “the Peninsula”: “Spain and Portugal together; Iberian Peninsula; Iberia.” Iberia would seem a rather odd exemplar for peninsulas, in fact. Blockish, clunky, and squat like the proverbial bull skin, its quadrangular or pentagonal morphology would seem to defy ipso facto its own definition as a three-sided landmass. What is important is that The Peninsula exceeds the toponymic register, rendering “Iberian” unnecessary and redundant, while peninsulas in Arabia, Korea, Indochina, and the Horn of Africa are denied the finality of the definite article. The majuscule of The Peninsula offers an even less subtle historical echo of European cartographic and imperial hegemony. Florida, Baja California, the Yucatán, and the Southern Cone are peninsulas once controlled by The Peninsula.

- Ceuta is a peninsula still controlled by The Peninsula.

¶ Where do peninsulas come from? The term derives from the Latin paenīnsula, or “almost an island.” California and its lower peninsula were long thought to be an island, a mythos that originated with Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo’s Las sergas de Esplandián. Yet Francisco de Ulloa’s circumnavigation of the peninsula in 1539 did little to dispel the islandic fantasy. It is as if peninsulas’ access to land severs them from the cachet enjoyed by islands. In the cultural imaginary, peninsulas occupy an in-between that offers neither the fanciful, idyllic isolation of an island nor the stability of a landlocked enclave; they are exposed to threats both terrestrial and maritime. Not unlike Sancho’s ínsula, peninsulas can be almost utopia and almost reality, but perhaps never fully either.

¶ What do peninsulas do? “Leaving a peninsula is not always easier than leaving an island,” Predrag Matvejević tells us, “because while the desire to leave is more readily realizable, it is also less final”[1] (A peripheral/peninsular question: What does it mean that almost all prominent peninsulas point downward on standard maps? What if they faced upward instead?) Even as they point, finger-like, toward other geographies, peninsulas underscore their own limits (pillars of Hercules, non plus ultra). These limits, and limit-situations, are both emphasized and elided in Iberia. Historically, its proximity to North Africa has made it a two-way bridge of both cultural exchange and domination, and to this day it is a tragically precarious gangplank to Europe. Yet the legacy of these exchanges have also segregated Iberia from Europe (encapsulated in perennial debates over the ‘difference’ of Spain and the racialized dismissal, often attributed to Dumas, that “Africa begins at the Pyrenees”). The narrow yet treacherous margins between it and surrounding continents—of water to its south, mountains to its north—mean that Iberia is dually connected yet disjointed, separate (from Europe / from Africa) yet linked (with Africa / with Europe). The (Iberian) Peninsula is at once an echt-peninsula and a pseudo-peninsula.

¶ Where does Peninsularism go? How should we think with these valences and affiliations of the peninsula? How might the singular contradictions of the Peninsula inform, reorient, and renew our discipline? How can Peninsularism’s historical status as marginalizing (e.g. vis-à-vis Latin Americanism) and marginalized (e.g. vis-à-vis other lettered traditions of the European mainland) afford us a useful vantage for making it less isolated and more inclusive? What viaducts, isthmuses, and jetties should Peninsularism build to engage other areas, or to assemble new geographical and archipelagic collectives? How, in short, to depeninsularize the discipline, to transpeninsularize our practice, to insulate Peninsularism from its own

- (pen)insularity?

Notes

- Predrag Matvejević, Mediterranean: A Cultural Landscape, trans. Michael Henry Heim (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1999), p. 20.[↑]