Etymology

¶ How appropriate that I become conscious of it in los Estados Unidos, where Spanishes are nearby, outside the window, in music strains hovering upwards from the passing cars, woven into remixed radio tunes. Judeoespañol makes itself known to me in a strange book, Las Aventuras de Alisia en el Paiz de las Maraviyas (2014). From the first j of its name – pronounced ž unlike in its more dominant Castillian cousin – I am in love. This Spanish of the Balkans delights me with little glimmers of Turkish running through it, or a candy-rock of Greek, flirting, winking, testifying to the Ottoman Empire that harbored the exiled Iberian Jews. A Renaissance Spanish that spent some time in Estambul, Salonik, Sarai, and Smirne, all places dear to my heart. It is a world that supposedly no longer exists or exists only in elderly voices, scratchy or digitally mastered recordings of music, sheaves of old newspapers, texts both sacred and profane, perfumed by Hebrew or French. It is a language, dead or alive, that brings several of my worlds together.

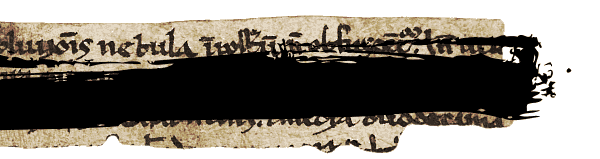

¶ I am no expert. My philological and literary-historical expertise, such as it is, lies further to the Northwest, in language varieties studded with thorns and yoghs. I am also unable to look at actual historical sources right now. Yale Library does not allow alumni memberships during the new pandemic school-year (2020–2021). Before I had to surrender my books in late August to SML, I had checked out a collection of writings by Laura Papo Bohoreta née Luna Levi (1891–1942), Mujer sefardí: cuentos, textos y poemas, edited by Nela Kovačević, and the massive, green hardcover Dictionnaire du judéo-espagnol (1977) compiled by Joseph Nehama and prepared for posthumous publication by Jesús Cantera. Now all I have is Avner Perez’s Alisia. How many people will read this book? What will the whimsical novel that like its heroine refuses to stay in place but rather becomes too big or too small, antagonizing insane tea-party hosts, add to the world of judeoespañol? This glossator can only present some personal resonances.

¶ When the White Rabbit appears, he is “un Taushan blanko,” from the Turkish tavşan. The orange marmelade is “DE PORTUKAL,” and Portugal indeed appears in that common Balkan (Albanian, Greek, Macedonian, Turkish) appelation for the fruit. One of the White Rabbit’s browbeaten servants, Pat, an Irish creature in the original, speaks with a “monasterlí” accent, pronouncing “un braso” as “ubrasu.” My heart beat fast when I saw that adjective. Nehama confirmed my instinct. Monastir/Manastir is Bitola in today’s Macedonia, a country whose official name has recently been augmented to North Macedonia. Битола, Manastiri, Битољ, Μοναστήρι, a town of many names, not an uncommon occurrence in the Balkans. Atatürk went to the Ottoman military academy there between 1896 and 1898. It hosted the Congress that standardized the modern Albanian alphabet in 1908. Through the Balkan Wars and the time of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, two Aromanian brothers Janaki and Milton Manaki, pioneers of their art, photographed and filmed many of its inhabitants. Bulgarian fascists deported almost the entire Jewish population of Bitola to Treblinka on March 11, 1943.

¶ Alisia does not hide her frustration with Wonderland, as I would not mine with History that leaves us with crumbs of lived reality, of real possibilities, in words: “Es el ziafet de te el mas estupido ke tenia visto en toda mi vida!” Most Spanish speakers can recognize everything but “el ziafet,” its meaning clear from its accompaniment “de te.” The word comes from the Turkish for feast, ziyafet, itself borrowed from the Arabic for receiving guests, hospitality. Ay, what can I do unconsoled amidst etymologies? “El argumento del djellat era ke es imposivle kortar una kavesa si no ay puerpo del ke kortarla.” Djellat, from the Turkish cellat, executioner, from the Arabic verb جَلَدَ “he scourged, he slapped.” History as an executioner. Language as a mysterious smiling cat that vanishes to reappear later.